When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

Scientists have discovered that dark matter, the universe's most mysterious "stuff," obeys gravity on vast cosmological scales. This could help to dismiss the possibility of a fifth fundamental force of nature — but even if not, it certainly puts restraints on that potential force's strength.

It's long been known that "everyday matter" is made up of atoms, which are, in turn, composed of protons, neutrons and electrons. We also know that these particles fall in line with the known fundamental forces of nature: electromagnetism, gravity, the strong nuclear force and the weak nuclear force. However, what has been less clear is whether dark matter obeys these same four forces. Indeed, one of the reasons dark matter is so puzzling is that it doesn't seem to act in conjunction with light, or electromagnetic radiation. And if it does, it does so much more weakly than ordinary matter does. This makes dark matter effectively invisible, meaning the only way scientists can infer its presence is by observing its gravitational effects and then watching how that acts as a middleman and impacts light and ordinary matter.

But determining that dark matter interacts gravitationally on relatively small scales, such as within galaxies, doesn't tell us if it obeys the well-understood laws of gravity as defined by Albert Einstein's 1915 theory of gravity, general relativity, on much larger cosmological scales. That is a big question because accounting for five times more of the matter in the universe than everyday matter, dark matter should have played a major role in how the cosmos developed.

To solve this conundrum and to discover if dark matter could be governed by a fifth, thus far unknown fundamental force, researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) set about determining if dark matter falls into cosmic gravity wells on vast scales just as ordinary matter does. These gravity wells are created when bodies of tremendous mass cause the very fabric of space and time, unified as a single four-dimensional entity called "spacetime," to warp (as established by general relativity). The greater the mass of the body, the more extreme the warping of spacetime, the "deeper" the resultant gravity well, and thus the stronger the gravitational influence.

"To answer this question, we compared the velocities of galaxies across the universe with the depth of gravitational wells," Camille Bonvin, team member and UNIGE researcher, said in a statement. "If dark matter is not subject to a fifth force, then galaxies — which are mostly made of dark matter — will fall into these wells like ordinary matter, governed only by gravity.

"On the other hand, if a fifth force acts on dark matter, it will influence the motion of galaxies, which would then fall into the wells differently. By comparing the depth of the wells with the galaxies' velocities, we can therefore test for the presence of such a force."

With this approach and using up-to-date cosmological data, the team established that dark matter does indeed slip into gravity wells just as ordinary matter does. While these findings provide no hints of a fifth fundamental force of nature, they can't absolutely rule it out.

"At this stage, however, these conclusions do not yet rule out the presence of an unknown force. But if such a fifth force exists, it cannot exceed 7% of the strength of gravity — otherwise it would already have appeared in our analyses," Nastassia Grimm, team leader and researcher at the Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, University of Portsmouth in the UK.

While these results don't close the book on a fifth force of nature governing dark matter, they do help better define the characteristics of this disturbingly elusive form of matter. And if there is a fifth force of nature, it likely won't be able to hide forever.

"Upcoming data from the newest experiments, such as LSST [the Legacy Survey of Space and Time conducted by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and DESI [the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument], will be sensitive to forces as weak as 2% of gravity," Isaac Tutusaus, team member and researcher at the University of Toulouse, said. "They should therefore allow us to learn even more about the behaviour of dark matter."

The team's research was published on Monday (Nov. 3) in the journal Nature Communications.

LATEST POSTS

- 1

CDC advisory panel delays vote on hepatitis B vaccines after unruly meeting

CDC advisory panel delays vote on hepatitis B vaccines after unruly meeting - 2

Putting resources into Yourself: Self-awareness Techniques

Putting resources into Yourself: Self-awareness Techniques - 3

Sound and Delightful: 12 Nutritious Smoothie Recipes

Sound and Delightful: 12 Nutritious Smoothie Recipes - 4

Charli xcx teases new film ‘The Moment’: What to know about the A24 movie

Charli xcx teases new film ‘The Moment’: What to know about the A24 movie - 5

Instructions to Decide the Best SUV Size for Seniors

Instructions to Decide the Best SUV Size for Seniors

Purdue Pharma's deal means money for some victims, end of Purdue company name. Here's what to know

Purdue Pharma's deal means money for some victims, end of Purdue company name. Here's what to know Israel violated ceasefire with Hezbollah more than 10,000 times, UNIFIL claims

Israel violated ceasefire with Hezbollah more than 10,000 times, UNIFIL claims Step by step instructions to Pick A Pre-owned vehicle Stage

Step by step instructions to Pick A Pre-owned vehicle Stage Fascinating Fishing Objections From Around The World

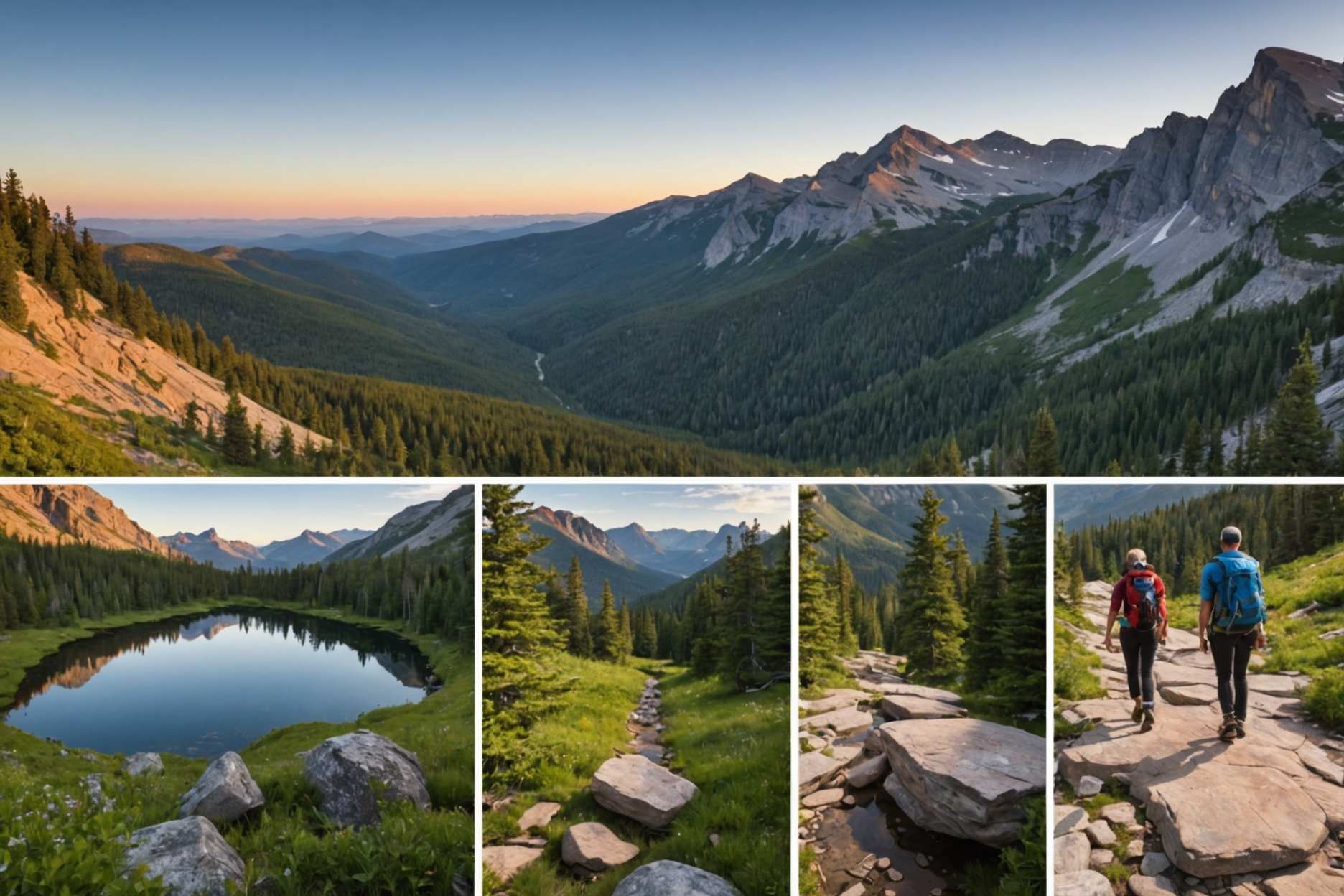

Fascinating Fishing Objections From Around The World 6 U.S. States for Climbing

6 U.S. States for Climbing Figure out How to Modify Your Pre-assembled Home for Greatest Solace and Stylish Allure

Figure out How to Modify Your Pre-assembled Home for Greatest Solace and Stylish Allure The most effective method to Plan an Incineration Administration: A Bit by bit Guide.

The most effective method to Plan an Incineration Administration: A Bit by bit Guide. Instructions to Back Your Sunlight powered chargers: Tracking down Possible Choices

Instructions to Back Your Sunlight powered chargers: Tracking down Possible Choices 'We need everyone,' wounded reservist urges Knesset panel to advance haredi draft law

'We need everyone,' wounded reservist urges Knesset panel to advance haredi draft law